Pruning

Before setting out to prune your trees, it is important to understand your ultimate goals. Pruning can increase your enjoyment of your trees, but it will not necessarily increase their lifespan. Remember: your tree has lasted this long without a visit from your loppers! And making sure your orchard is receiving adequate water is more important to keeping it alive than providing it with a clean trim.

Learning the basics of pruning is an important first step to understanding how your cuts will affect the growth of your tree overtime. Young or old, where and how you cut your tree will invoke different responses from the tree, and there are vital techniques you must learn before you can achieve the response you want.

There are several valuable resources online and in your community to give you the basic knowledge needed to prune your tree to achieve your goals. For more general information on pruning fruit trees, the following resources are a great place to start:

- Watch this MSU Extension Video detailing basic pruning principles for fruit trees;

- Review one of several existing Extension publications on pruning trees, including this OSU guide on Training and Pruning Your Home Orchard;

- Most importantly, get first-hand experience. Take a pruning class or ask someone with more extensive pruning experience to teach you these techniques on an actual tree. If in-person learning isn’t on option for you, just be sure to start slow and make some experimental cuts that you can observe over the course of a season. Notice how these cuts influence your tree’s growth, paying special attention to the direction any new growth takes, and make future pruning decisions based on those results.

Now, back to your heritage orchard. The two most common reasons for pruning heritage trees are to increase the quality and quantity of fruit production, and to improve overall aesthetics. Additionally, if you would like to propagate new trees from a favorite heritage tree via grafting, pruning can help the mature tree to produce the young vegetative wood required for propagation (though so can a good soak).

Regardless of your high-level goals for pruning your tree, there are some basic rules that should be followed before making the more strategic cuts:

- Do not remove more than one third of the living vegetation in a season.

- Prune when trees are dormant. In Montana, this window typically falls between December and the end of March.

- Remove dead, diseased, crossing, and vertical (water sprout) branches first. Then remove suckers from around the base of the tree. To completely remove suckers and water sprouts, use a “thinning cut” (see figure below on left). To encourage targeted growth of new branches, choose an outward facing bud and make a “heading cut” (see figure below on right). For more information on these pruning techniques, review the resources previously mentioned.

Example of a thinning cut.

Example of a heading cut.

After you have completed these initial steps, your pruning cuts become dependent on your higher goals. To increase fruit quantity and quality, you will want to adopt a tree form that allows for easy management and harvest. This means thinning out crowded lower limbs so that branches can sink down lower (once laden with fruit), allowing for easier harvesting access. Additionally, removing branches that crowd lower limbs allows for better sunlight penetration through the tree's canopy, which helps ripen the tree's fruit and boosts its collection and storage of sugars through photosynthesis. Reducing crowded limbs also encourages airflow through the canopy, helping reduce the spread of disease.

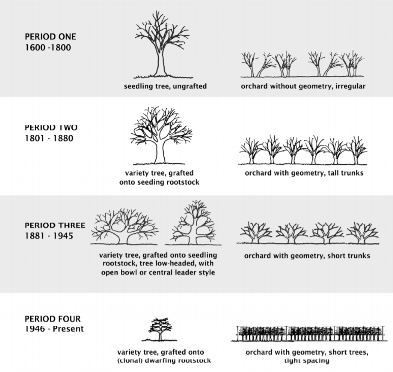

Diagram of changes in tree and orchard forms over four periods of American apple production (S. Dolan).

If you are pruning for historical aesthetic, you should consider the form a tree may have taken during the period it was originally planted. In her guide, Fruitful Legacy, Susan Dolan describes the evolution of tree form and pruning techniques from 1600 to the present. Most Montana heritage trees were planted during Periods Two and Three, when trees either branched from a straight trunk well above the ground or were pruned to an open vase form, as depicted in the figure to the right.

Your trees will likely provide you with clues as to what form they were intended to take, and your pruning decisions should support this form rather than work to drastically change it. For example, in the photo below on the left, this tree was never pruned to an open vase, but instead has grown more geometrically from a tall trunk (Period Two). The orchard pictured to the right, on the other hand, was pruned in the open vase (or “open bowl” form), which was popularized with commercial orchards in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Example of a tall vertical trunk form.

Example of an open vase form.

The more structurally sound form is that of the central leader (left), which is why it became more popular overtime. The open vase form, however, tends to be what we think of most when imagining a heritage orchard. To achieve this aesthetic, trees must be carefully pruned so as not to remove too much vegetation in one year, and interior and vertical limbs should be removed to open up the tree’s center.

Remember, your tree took decades to grow to the form it is now, so don’t try to change it too drastically over the course of one dormant pruning. Take it slow and give the tree time to respond. And as we’ve mentioned, a little water never hurts!