Precision Ag Update - January 2026

Variable Rate Technology for Precision Farming

Written by: Safal Adhikari, Clain Jones and Anish Sapkota, January 2026

Summary

This article explains variable rate technology as a key component of precision agriculture that allows farmers to apply inputs such as seed, fertilizer, herbicides, and water at rates that match field variability, rather than using uniform applications. It describes map-based and sensor-based approaches to variable rate application and highlights common practices such as variable rate seeding, fertilization, herbicide, and irrigation.

What is Variable Rate Technology?

Precision agriculture is a management strategy that helps identify and address spatial and temporal variability in soil, crops, livestock, and the environment. It uses data-driven decisions to optimize agricultural inputs and improve efficiency, productivity, quality, profitability, and long-term sustainability of farm operations (ISPA, 2024). Variable rate technology (VRT) is a key component of precision agriculture. It allows growers to adjust inputs such as seed, fertilizer, pesticides, and irrigation water at different rates across a field based on measured field variability, without manually changing rate settings or making multiple passes (He, 2023). In contrast, uniform application methods apply a single rate of inputs across the entire field, ignoring field variability. This often results in under-application or over-application of inputs in different areas of the field, leading to wasted resources and reduced efficiency (Pinto et al., 2025).

What are the types of variable rate technology?

Variable rate application (VRA) can be achieved through two main types of VRA: a) Map-based and b) Sensor-based.

a) Map-based variable rate application:

Map-based VRT is the most widely used approach for variable rate applications. It relies on geo-referenced data to create prescription maps that determine where and how much of a given input should be applied. These prescription maps can be developed using one or multiple data sources, including soil sampling results, proximal sensor data such as apparent electrical conductivity, vegetation indices such as normalized difference vegetation index from aerial remote sensing using drones or satellites, and yield monitor data. These data layers represent soil and crop attributes that influence yield and quality and are used to identify variability within a field.

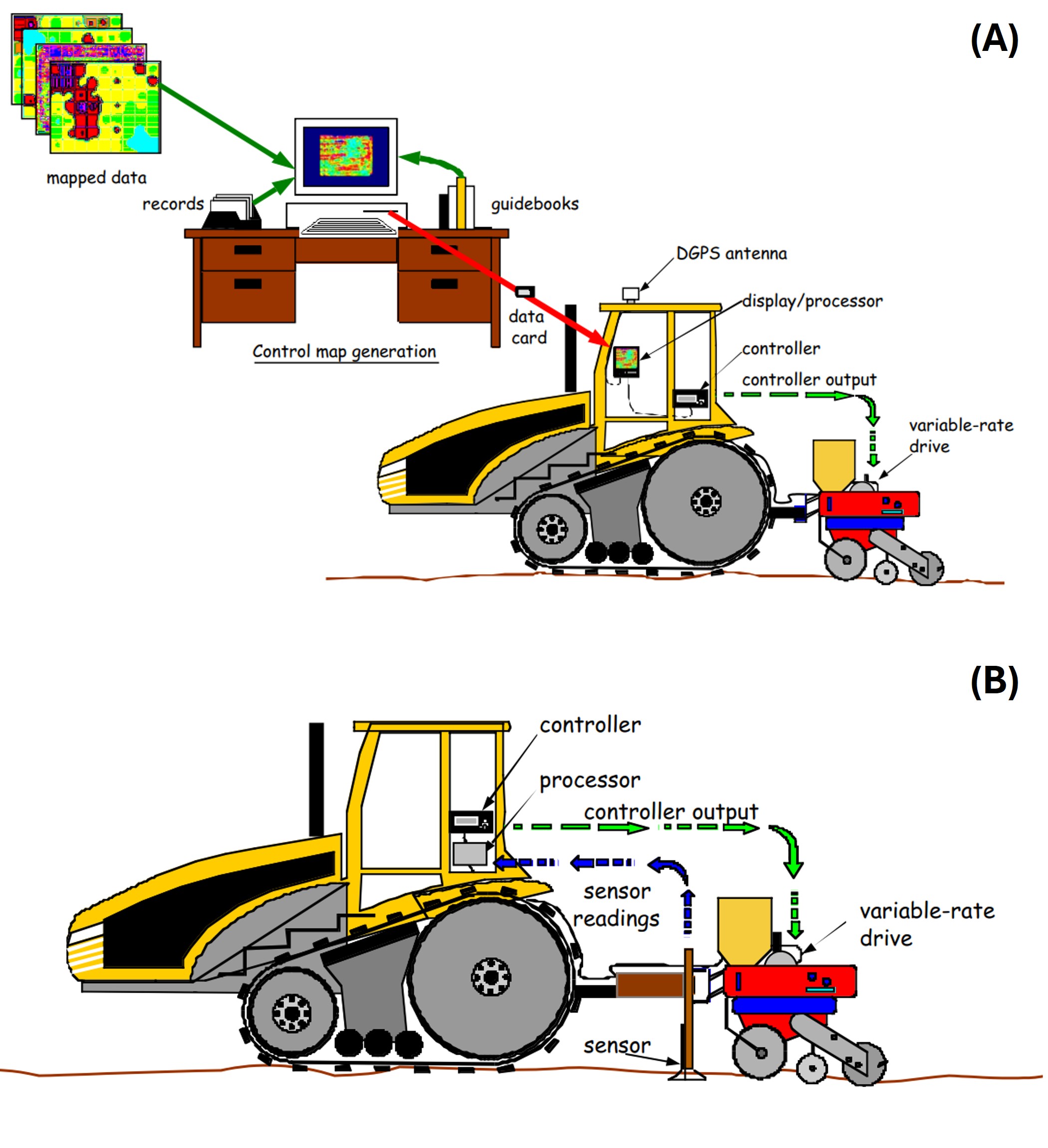

Map-based methods help growers accurately characterize field variability, develop reliable prescription maps, and plan input requirements such as total quantities and application rates in advance (Ess et al., 2001). However, map-based prescriptions, especially those relying heavily on soil sampling, may have coarse spatial resolution and can be time-consuming, labor-intensive, and costly. Adopting map-based VRA typically involves several steps, including data collection, geo-referencing and validation, understanding field variability, defining management zones, assigning variable input rates to each zone, exporting the prescription map to the applicator, and completing the variable rate application. An example of map-based variable rate application is shown in Figure 1A.

In general, map-based VRA systems are available for most crop production inputs. Many

growers already have access to useful data sources such as yield monitor records that

can support management zone development. Multiple data layers, including soil, yield,

and proximal and remote sensing data, can be combined to improve decision-making.

Growers also have flexibility to adjust prescriptions as needed, and applicator speed

typically does not need to be reduced, making this approach practical for many crops

and input types (Ess et al., 2001).

b) Sensor-based variable rate application

Sensor-based VRA uses optical or other on-the-go sensors to measure soil or crop characteristics in real time. The information collected is immediately processed and used to control application rates during field operations, as illustrated in Figure 1B. This approach eliminates much of the post-processing and advance prescription development required for map-based methods.

Sensor-based systems generally reduce pre-application data analysis time and provide higher-resolution information than traditional sampling methods. Because measurement and application occur simultaneously, these systems are more dynamic and can respond immediately to changing field conditions. However, sensor-based VRA may require reduced operating speeds to allow sufficient time for sensor data collection, processing, and decision-making. In addition, accurate in-field sensing technologies are needed to reliably distinguish soil and crop characteristics under varying conditions (Ess et al., 2001; Sharma et al., 2025).

Figure 1. Illustrations showing (A) map-based and (B) sensor-based variable rate technology systems for variable rate application. Pictures adopted from Ess et al., 2001. Available here (accessed on 01/03/2026)

Variable rate applications

Variable rate application (VRA) is a precision farming approach that uses variable rate technology to adjust the rate of inputs applied across a field. The following sections briefly discuss variable rate application of seed, fertilizer, herbicide, and irrigation in agriculture:

- Seeding: Seeding rates across the field can be adjusted based on variability in soil properties such as water-holding capacity, nutrient levels, organic matter, soil depth, and slope, as well as yield to improve crop production per acre (He et al., 2019; Šarauskis et al., 2022). Conventional planters and drills can be adapted for variable rate seeding by changing the speed of the seed-metering drive (Grisso et al., 2011). With the adoption of hydraulic and electric drive seed meters, seeding rates can now be controlled independently of ground speed, allowing for more accurate and responsive seed placement (Sharda et al., 2018).

- Fertilizer: Fertilizer is a critical input for crop growth and productivity, but nutrient availability and uptake are influenced by several factors, including soil texture, pH, structure, soil moisture, drainage, aeration, and soil temperature. These factors often vary within a field, between fields, and over time. Variable rate fertilizer application addresses this variability by adjusting fertilizer rates across the field (Schumann, 2010). This site-specific approach improves nutrient use efficiency by reducing over-application in some areas and under-application in others, helping growers optimize input use and crop performance.

- Herbicide: Weeds in agricultural fields typically occur in aggregated patches rather than being uniformly distributed, often infesting only 20 to 40% of a field (Gerhards and Christensen, 2003; Timmermann et al., 2003). Uniform herbicide application that ignores this spatial variability can result in overuse of chemicals in weed-free areas and inadequate control in areas with dense weed patches. Variable rate herbicide application addresses this issue by applying different herbicide doses across the field based on weed density. Depending on the technology available, this approach can be implemented using either map-based or sensor-based systems. The goal of variable rate herbicide application is to improve weed control efficiency while reducing input costs and environmental risks (Costa Lima and Mendes, 2020).

- Irrigation: Variable rate irrigation applies different depths of water across a field. Water requirements are affected by factors such as soil type, precipitation, crop growth stage, crop, solar radiation, and wind speed. The primary goal of variable rate irrigation is to increase water use efficiency by applying water where and when it is needed (Sharda et al., 2018; Sapkota et al., 2025). Depending on the irrigation system, variable rate irrigation can be implemented using sector control or zone control. In sector control, the speed of a center pivot system is adjusted while the application rate remains constant, resulting in different water depths across the field. In zone control, the field is divided into homogeneous zones, and individual sprinklers or groups of sprinklers are controlled using solenoid valves, allowing different water depths to be applied at specific locations.

Challenges of variable rate technologies

Variable rate technologies offer several advantages, including improved nutrient and water use efficiency, optimized seeding rates, reduced chemical input use, and progress toward more sustainable production systems; however, several challenges continue to limit their widespread adoption. Key barriers include high up-front equipment and technology costs, limited access to precision agriculture education and training, and difficulties associated with data collection, analysis, validation, and interpretation. Addressing these challenges will help to increasing adoption of variable rate technologies and precision farming practices more broadly (US-GAO, 2024).

References

Costa Lima, A. and K. Ferreira Mendes. 2020. Variable rate application of herbicides for weed management in pre- and postemergence. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.93558

Ess., D.R., M.T. Morgan, and S.D. Parsons. 2001. Implementing site-specific management: map- versus sensor-based variable rate application. #SSM-2-W. Purdue University Extension. Available at https://edustore.purdue.edu/ssm-2-w.html (accessed on 01/03/2026)

Gerhards, R. and S. Christensen. 2003. Real-time weed detection, decision making and patch spraying in maize, sugarbeet, winter wheat and winter barley. Weed Research, 43:385-392. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3180.2003.00349.x

He, L. 2023. Variable rate technologies for precision agriculture. In: Zhang, Q. (eds) Encyclopedia of Smart Agriculture Technologies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89123-7_34-3

He., X., Y. Ding, D. Zhang, L. Yang, T. Cui, X, Zhong. 2019. Development of a variable-rate seeding control systems for corn planters part II: field performance. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 162:309-317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.04.010

ISPA. 2024. Precision agriculture definition. International Society of Precision Agriculture. Available at https://www.ispag.org/resources/definition (accessed on 01/03/2026)

Pinto, R., A. Sapkota, P. Nugent, and S. Wyffels. 2025. Precision agriculture: concepts and opportunities for Montana producers. MontGuide #MT202502AG. Montana State University Extension. Available at https://www.montana.edu/extension/montguides/montguidehtml/MT202502AG.html (accesses on 01/03/2026)

Sapkota, A., M. Roby, S.R. Peddinti, A. Fulton, and I. Kisekka. 2025. Comparative analysis of evapotranspiration (ET), crop water stress index (CWSI), and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) to delineate site-specific irrigation management zones in almond orchards. Scientia Horticulturae, 339:113860 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113860

Šarauskis, E., M. Kazlauskas, V. Naujokienė, I. Bručienė, D. Steponavičius, K. Romaneckas, and A. Jasinskas. 2022. Variable rate seeding in precision agriculture: recent advances and future perspectives. Agriculture, 12:305. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12020305

Schumann, A. W. 2010. Precise placement and variable rate fertilizer application technologies for horticultural crops. HortTechnology, 20:34–40. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH.20.1.34

Sharda, A., A. Franzen, D.E. Clay, and J.D. Luck. 2018. Precision Variable Equipment. In Precision Agriculture Basics (eds D. Kent Shannon, D.E. Clay and N.R. Kitchen). https://doi.org/10.2134/precisionagbasics.2016.0094

Sharma., V., U.B.P. Vaddevolu, S. Bhambota, Y. Ampatzidis, H. Bayabil., and A. Singh. 2025. Variable rate technology and its application in precision agriculture. AE607. University of Florida IFAS Extension. https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ae607-2025

Timmermann, C., R. Gerhards and W. Kühbauch. 2003. The economic impact of site-specific weed control. Precision Agriculture 4:249–260. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024988022674

US-GAO. 2024. Precision agriculture: benefits and challenges for technology adoption and use. United States Government Accountability Office. GAO-24-105962. Available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-105962 (accessed on 01/03/2026)

Get Connected & Learn More

Safal Adhikari

MSU Graduate Research Assistant

Dr. Clain Jones

Professor

Dr. Anish Sapkota

Assistant Professor

(406) 994-5712

anish.sapkota@montana.edu