Fort Assinniboine

Fort Assinniboine1879-1911

"Assini boise" from the Objiway (Chippeewa) tribes, meaning: stone cookers/stone boilers

Mission

Fort Assinniboine was built in the aftermath of the Custer disaster at the Little Big Horn. It was primarily established to ward off possible attacks by Sioux Chief Sitting Bull and by the Nez Perce.

There were secondary reasons for the structure. General William Sherman had envisioned a line of forts near the northern and southern boundaries of the United States. When starving Indians pressed south from Canada pursuing buffalo, cattlemen, miners and other settlers pressured for federal troops to intervene. Control of the Blackfeet Reservation and protection of trade routes were additional reasons for the fort.

Construction

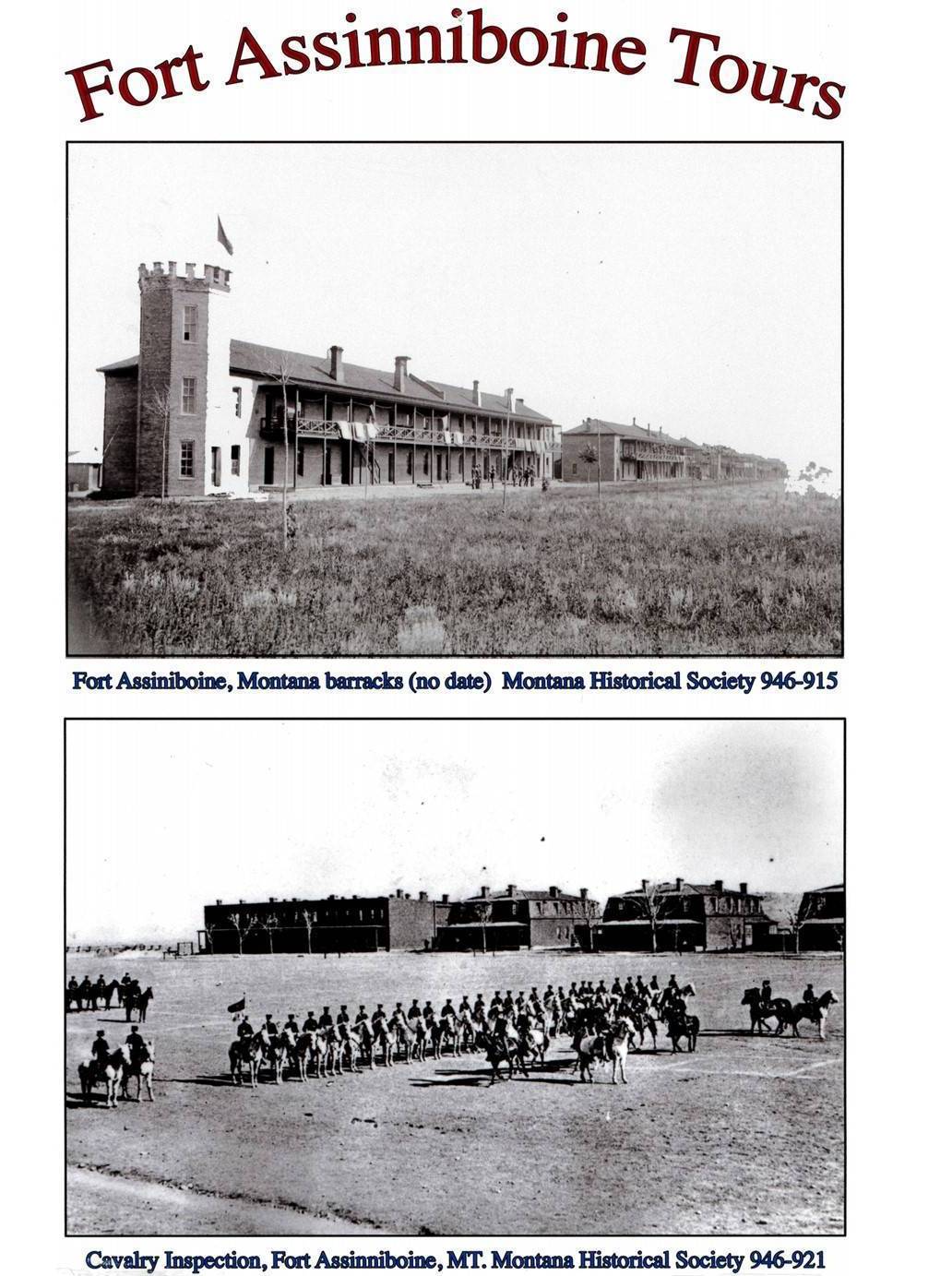

At the time of construction, Fort Assinniboine was the most elaborate post in the United States. Unlike earlier frontier posts, it was an offensive fortress and had no perimeter wall. The rectangular post eventually boasted 104 buildings constructed over a four-year period. L.K. Devlin was selected to undertake construction. The bricks were manufactured on the spot by Colonel C. S. Broadwater. Much of the work was done by the troops themselves. At its peak, the Fort housed 36 officers and 453 non-commissioned officers and enlisted men.

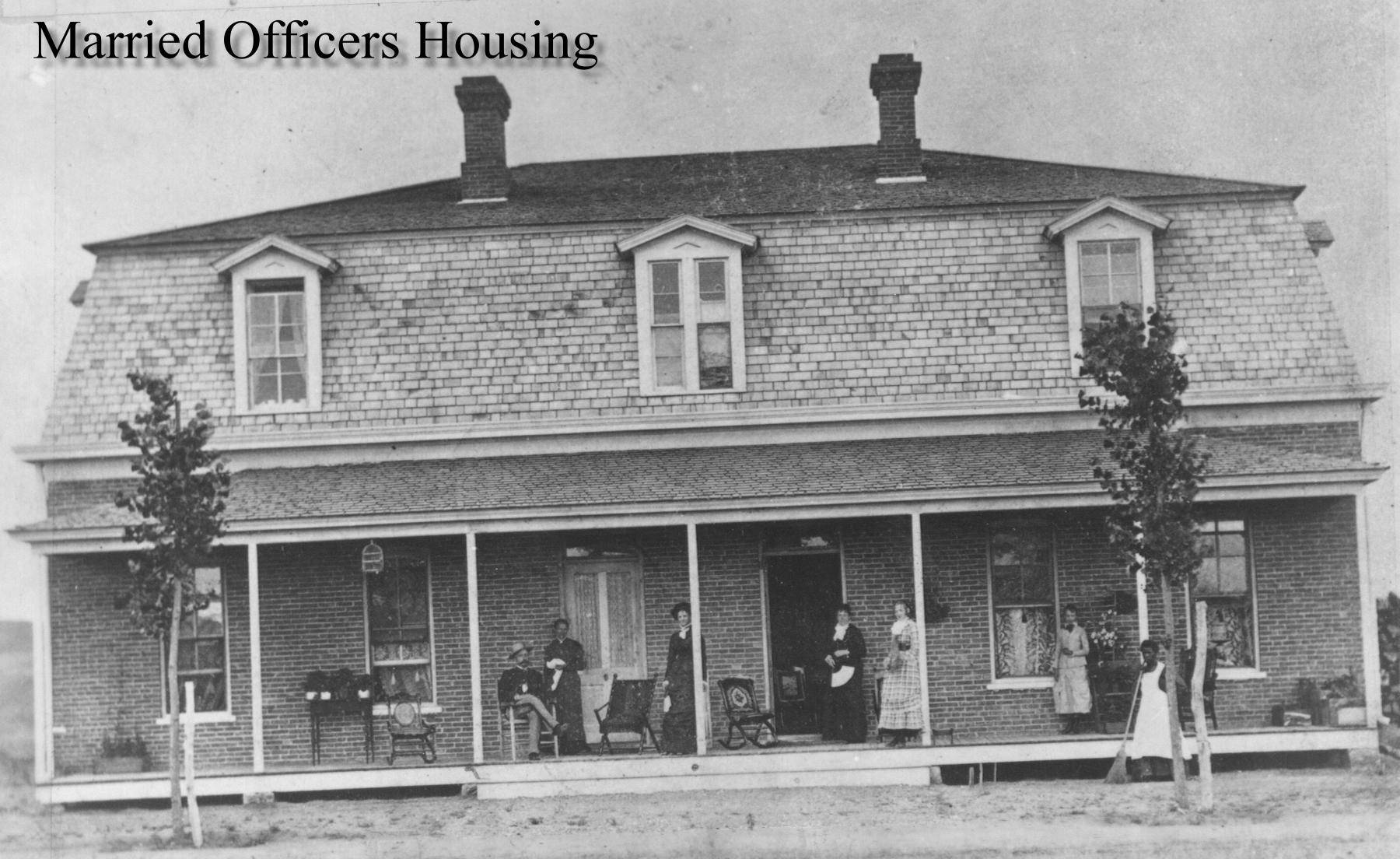

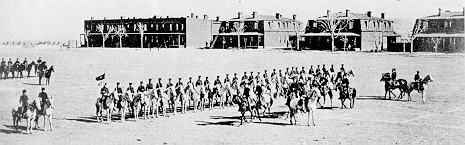

Officer's Quarters, Al Lucke Collection 10th Cavalry "Buffalo Soldiers" on escort duty 1894

Soldiers

The Tenth Cavalry was dubbed the Buffalo soldiers by the Cheyenne Indians, who respected their fighting abilities and likened their strength and courage to the sacred buffalo. These men were given the worst mounts in the cavalry, and because of their race, had no chance to become officers. The 24th and 25th Infantry black units were also stationed at Fort Assinniboine. The Fort had a multi-racial force that included Black, Native and white soldiers.

Typical assignments included recovering lost mounts, scouting for Indians, burning their shacks and escorting the starving people to the border. The Milk River Valley had become a battleground between warring tribes, (Blackfoot nation, Plains Cree and Sioux); Fort Assinniboine troops took an active role in curtailing these clashes.

Elite cavalry unit leads a drill at the recently completed Fort Assinniboine.

Officers

Several prominent men served at, or were connected with the Fort. These included generals Ruger, Brooke and Otis. Colonel J.K. Mizner, C.O. of the 10th Calvary, had been a highly decorated Civil War hero. The most famous officer to serve at the Fort was John J. (Black Jack) Pershing, who voluntarily arrived in 1896 with the Tenth Cavalry, a black regiment. During his time at Assinniboine, he accomplished two notable things. He impressed visiting dignitary, Major General Nelson Miles, and he laid the foundation for his future nickname “Blackjack.”

|

|

General John J. (Black Jack) Pershing

|

After the failure of the Riel Rebellion in 1885, several hundred Cree Indians led by Little Poplar and Little Bear settled around the Fort. They were given political asylum from their Canadian crimes. They were given food and work cutting wood. When cutting wood was banned for conservation reasons, and other work dried up, Chief Little Bear’s tribe scattered.

In 1895 and 1896, the anti-Cree campaign was intensified. The Cree were not recognized as US citizens and were squatters on land given by treaty to the Gros Ventres. Pershing participated in the roundup of several hundred homeless Cree Indians under Chief Little Bear, and escorted them back to a temporary home in Canada. Lieutenant Letcher Hardeman took a detachment to round up Crees near Chinook. Eventually the Cree found a home on the Rocky Boy’s Reservation carved out of Fort property in 1916.

After the war against Spain, Fort Assinniboine never regained its military preeminence. The post was abandoned in 1911, the State of Montana turned the site into an agricultural experiment station.

Civilians

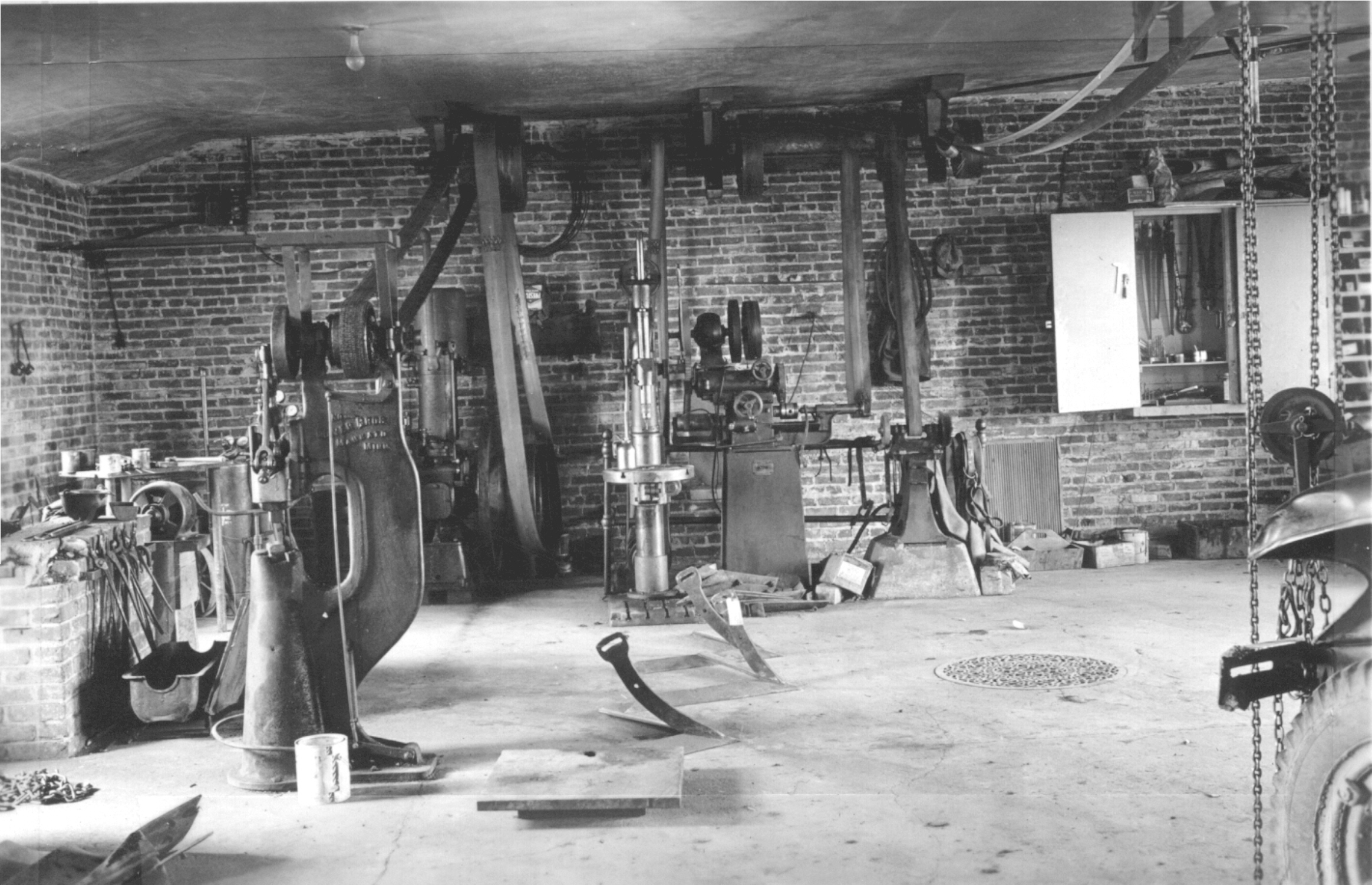

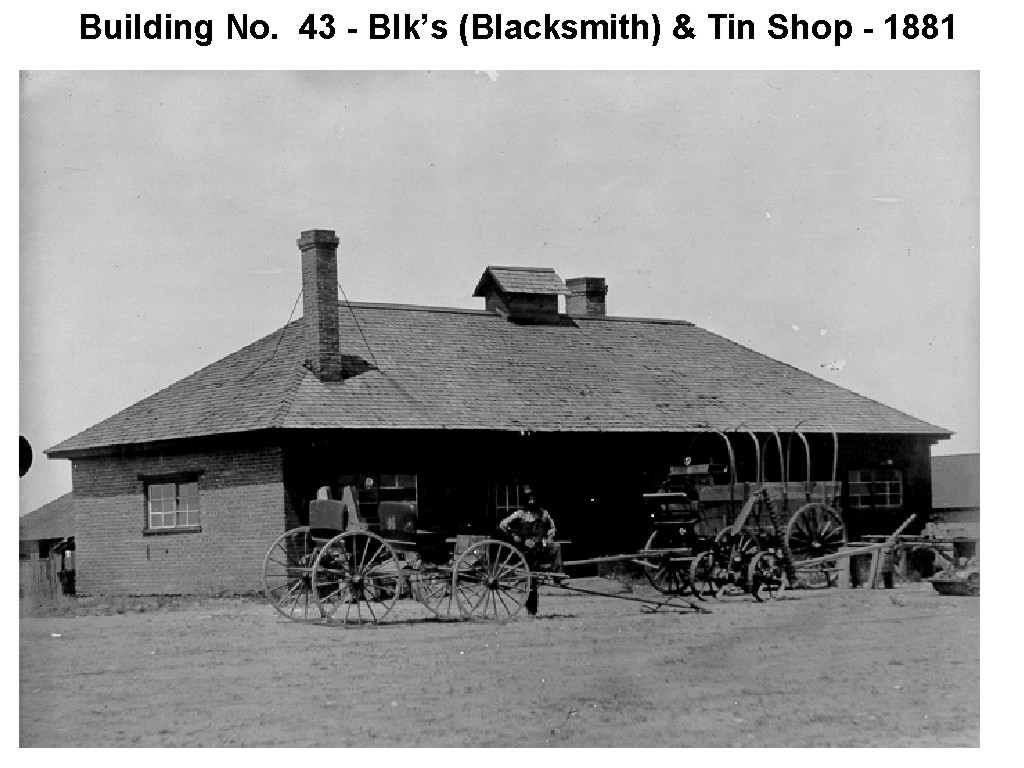

The Fort’s remote location dictated that it be practically a self-contained town. There were several specialty buildings located on Fort Assinniboine - blacksmithing, wagon wheel making, and saddlery - all operated by civilian employees. Familiar Havre names associated with the Fort include Simon Pepin, who had been wagon master for Colonel Broadwater’s Diamond R freighting outfit, and Louie Shambo who acted as scout and dispatch carrier. The Herron family established a dairy just east of the post and William Thackeray delivered mail. L.K. Devlin had the contract for supplying the post with meat. C.A. Broadwater and Co. had the post store.

|

|

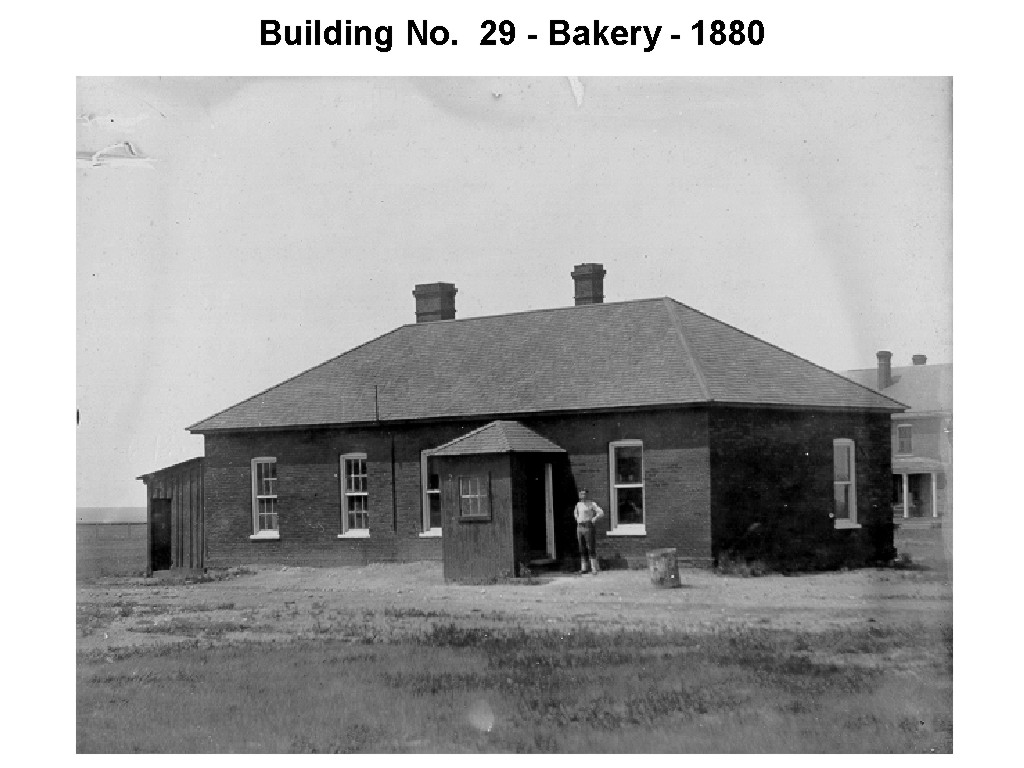

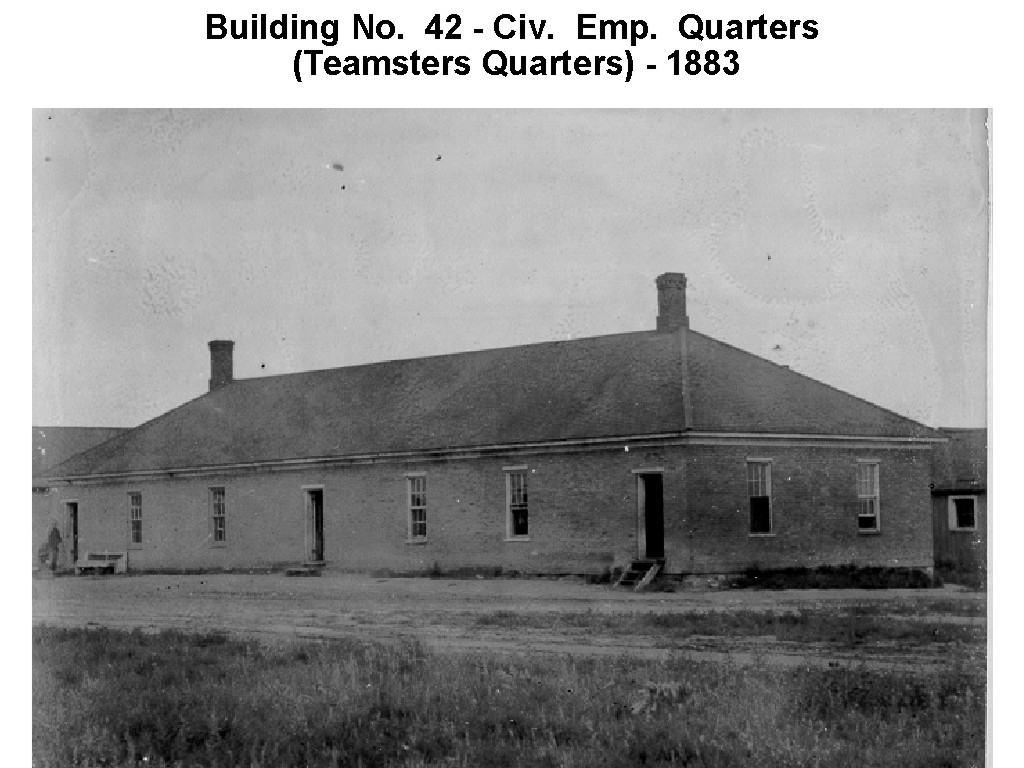

| Civilian Employee's Quarters, 1883 | Bakery, 1880 |

|

|

| Blacksmith & Tin Shop | Inside Blacksmith Shop |

Acknowledgements

- Hardeman, N.P. 1979. Brick Stronghold of the Border: Fort Assinniboine, 1879-1911. Montana The Magazine of Western History, Vol. XXIX, No. 2, April 1979, The Montana Historical Society.

- Magera, James. Archives.

- Fort Assinniboine Preservation Association.

- Photographs: Al Lucke Collection, Montana Historical Society.